Restoring landscapes and preserving ecosystems—even as major construction is taking place—is a call landscape architect Tom Berger, ASIA, has answered for 25 years. It was that long ago that his firm, the Berger Partnership, began daylighting and restoring creeks in Seattle neighborhood park projects. At IslandWood, Berger was able to translate a long-held passion for restoration and regeneration of natural systems into a teaching and learning environment.

'The idea was to make the least impact on the land—and yet make the most profound statement about the land,' says Berger. His firm had worked with the architectural firm Mithunon the REI corporate headquarters building in Seattle, which brought a little of the forest hack into the city and won widespread recognition for sustainable design (see "Street Corner Wilderness," Landscape Architecture. July 1999). Both the Berger Partnership and Mithun were handpicked by IslandWood founder Debbi Brainerd to demon-saute sustainability at the learning center. They worked as a team from the scan of the project in the fall of 1997 until completion in the summer 42002, with Berger primarily responsible for site planning and restoration.

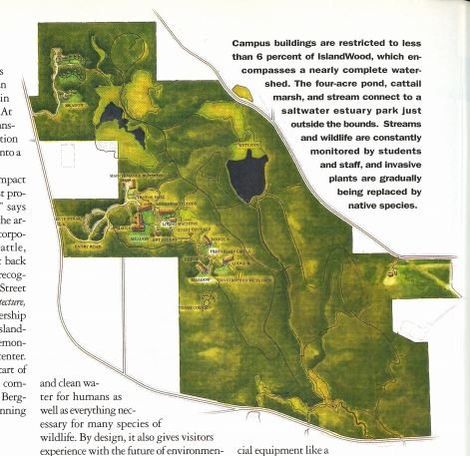

Campus buildings are restricted to less than 6 percent of IslandWood, which encompasses a nearly complete watershed. The four-acre pond, cattail marsh, and stream connect to a saltwater estuary park just outside the bounds. Streams and wildlife are constantly monitored by students and staff, and invasive plants are gradually being replaced by native species.

Biomass basics, IslandWood style

Nearly 100 percent of the biomass of the site was retained at IslandWood throughout the restoration project. This achievement, which helped the project to win the coveted gold LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) rating from the U.S. Green Building Council, was made possible by several measures built Into the construction process:

- Harvested wood, snags, and forest floor duff were stockpiled during construction. New planted areas are mulched with chipped green waste material.

- Site restoration included the location and eradication of invasive plant species and re-vegetation with native plants. many of which were salvaged during construction.

- Rock piles and brush piles made of site-salvaged logs and branches encourage the presence of wildlife.

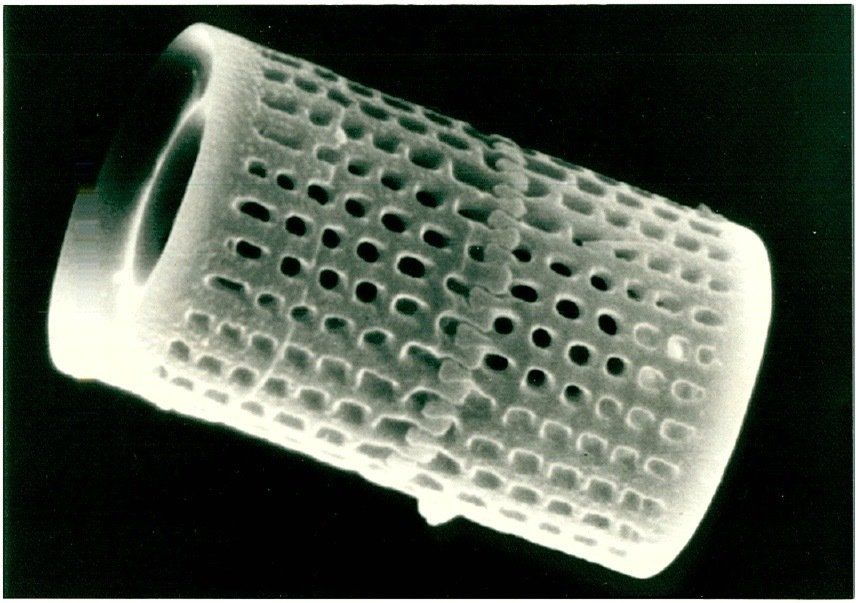

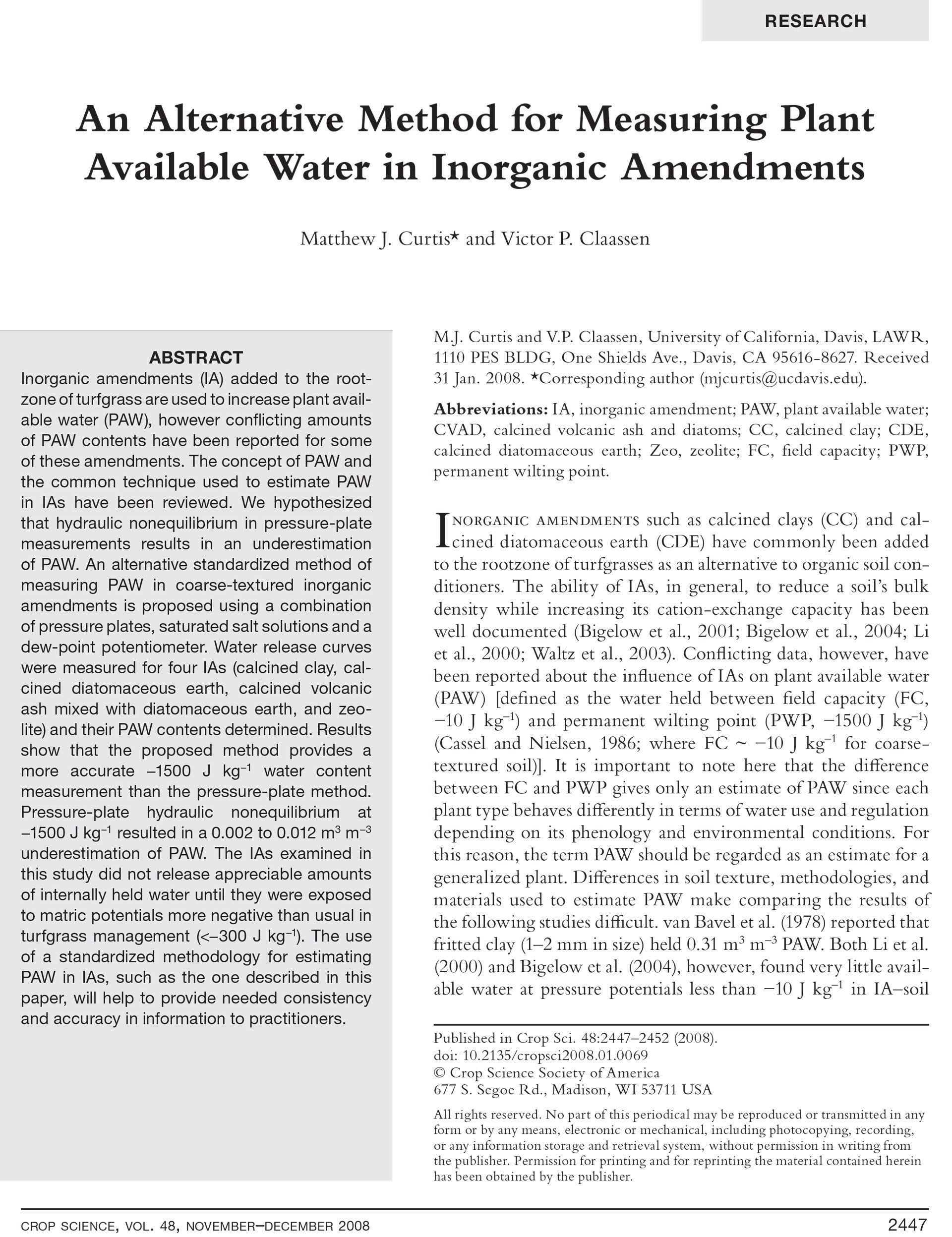

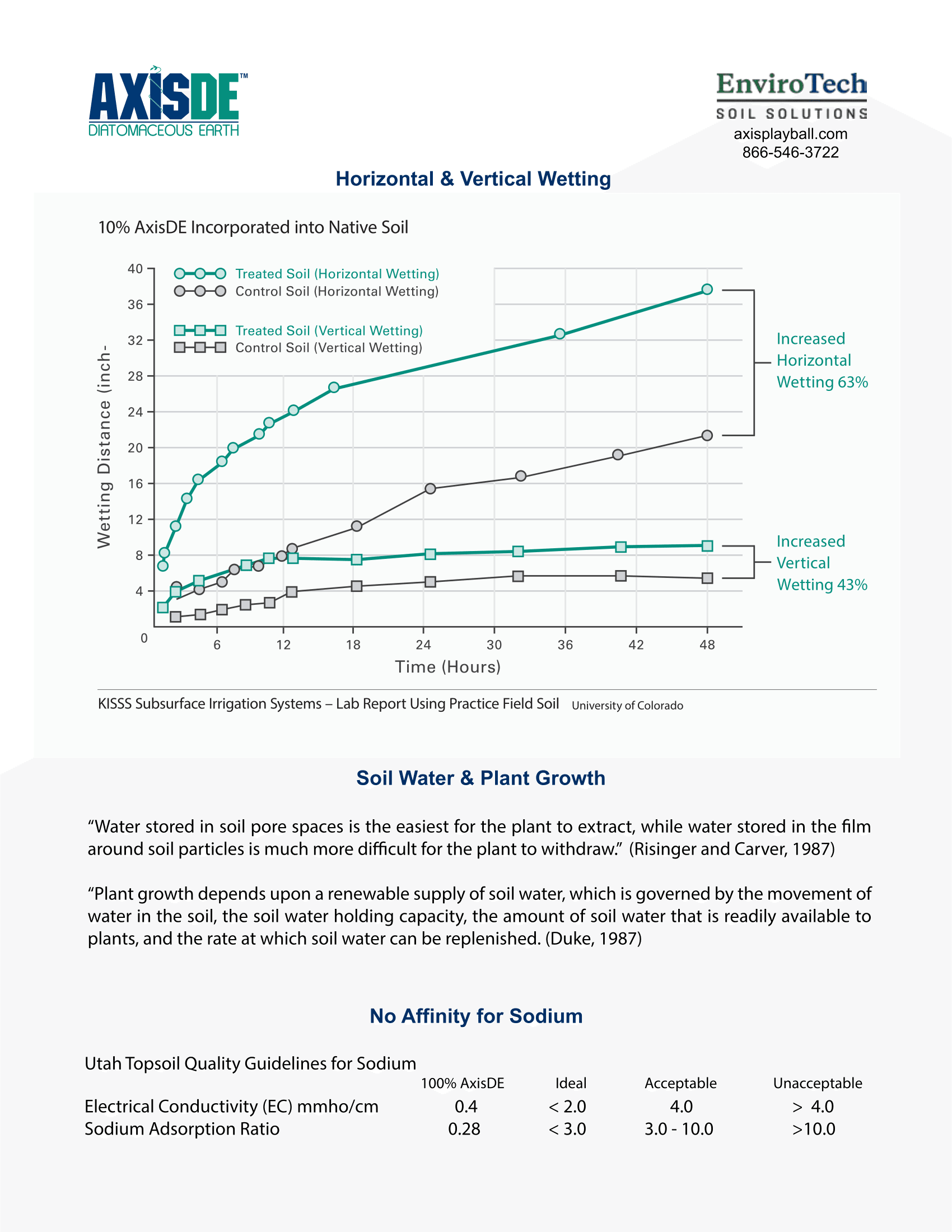

- Salvaged topsoil is amended with diatomaceous earth to increase water retention and eliminate the need for a permanent irrigation system.

Propagated and reintroduced native plants were able to take advantage of the rhizomes and microorganisms naturally present in the retained forest floor duff to quickly reestablish themselves.

A Sustainable Worldview

Now in its second summer of operation, IslandWood provides a window on a whole ecosystem at work—providing food and clean water for humans as well as everything necessary for many species of wildlife. By design, it also gives visitors experience with the future of environmental science and technologies, with professional staff to show the way.

The typical IslandWood student is 11 years old and carries a small pack with special equipment like a pH testing kit, a measuring tape, a float for calculating stream velocity, forms, pencils, a sketch pad, and maybe a calculator. Gathered data will be entered into a system set up to monitor water quality in the small creeks on site, and it may be used to generate a presentation on environmental science back at school in the city. Some classes go on to test more streams in their own neighborhoods.

The kids listen to local storytellers and make up some stories of their own, draw sketches of wildlife, play charades, and read their poetry around the campfire. They take their food wraps out to the compost bin, where they learn vermiculture in the organic garden.

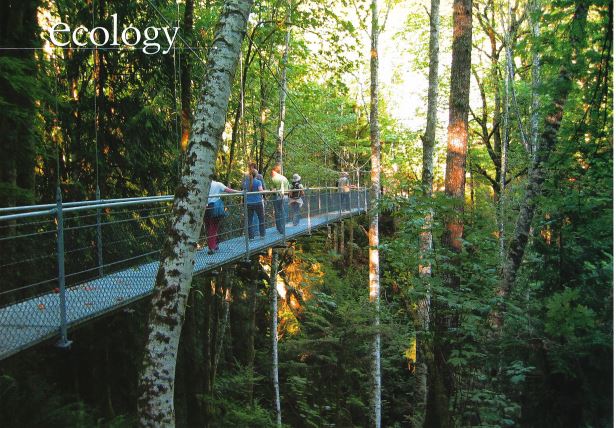

While much of the curriculum is in the woods, education also takes place in the laboratory, in the kitchen, and in the studio. The campus includes a central lodge with reception and assembly areas, a dining hall, educational studios, a creative arts studio, and sleeping lodges. Special field structures, including a suspension bridge, forest canopy tower, floating classroom,bird blind, mill worker's cabin, and tree houses, enrich the learning environment.

"The center is a magical place where children and visitors can develop greater understanding of the Puget Sound native ecology—and reduce their own ecological foot-print," says Berger.

Design team members from Mithun and the Berger Partnership camped on site with the client at the outset of the project, hacking through invasive blackberry brambles on the former tree farm and making a map of opportunity and imagination.

The dream was to link constructed and natural systems in new and interdependent ways, building in the means of regeneration and renewal. And the reality is now a hardworking environmental laboratory. At the center of the campus is the glass-enclosed "Living Machine," a wastewater treatment facility char treats blackwater using natural processes. Pipes and wetland cells are exposed to view so that children can experience and intuitively grasp the workings of the system. Water used for a flush toilet and for watering of nonfood plants is returned to the system for cleaning and leaves the greenhouse visibly clear.

At lodge entrances, the design team used logs salvaged from the former tree farm's holdings and boulders salvaged from construction. A crushed, recycled concrete aggregate base course Is used for paths and paving.

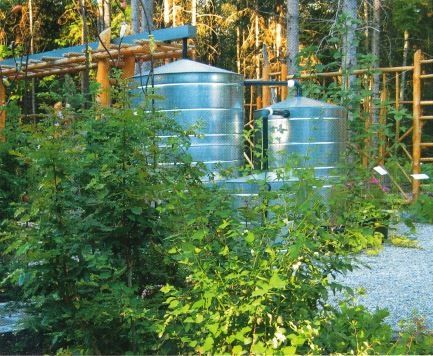

The organic garden with raised beds, a green-house, a composting bin, a water-harvesting system, and demonstration areas provides an outdoor classroom and laboratory for cultivating food plants. Food grown in the garden is harvested by students and staff and used in meals prepared at the center, and scraps are composted and brought back to the planting beds. The garden nursery is used to propagate native plants and reestablish them in the areas where invasive species were removed.

Natural landscape and lodges are intimately connected at IslandWood, where clearing of trees was restricted to 15 feet outside building perimeters. Much of the second-growth forest has been carefully restored to natural conditions. Recovered forest duff is scattered over mulched areas near new plantings.

Designing for Nature

Building a campus for hundreds of out-of-town students was not an easy sell for Bainbridge Island, where many have chosen to live for its rural setting. Although the tree farm years had degraded the forest environment with chainsaws, tractors, and crash, the neighbors had enjoyed freedom of access to the IslandWood site. Generations of local kids had grown up exploring the forest and swimming in "Mac's Pond" there.

Opposition to the project was finally put to rest through assurances about noise and traffic disruption, as well as the knowledge that the site was sure to be developed anyway. Island Wood would be an environmental asset, a resource for local schools, and a good neighbor. The same group chat originally voiced objections finally helped in the exhaustive process of identifying, inventorying, and weeding out invasive and nonnative species on the site.

The boundaries of the property en-close a nearly complete watershed with a wildlife habitat, salmon spawning streams, and a rich diversity of ecosystems, which include a four-acre pond, cattail marsh, bog, scream, and dramatic ravine. There's access to an adjacent salt-water estuary park.

With IslandWood—as with many sites—finding the place where the man-made landscape ends and nature begins is a difficult proposition. The land, a thrice-logged tree farm and second-growth for-est, had an artificial lake that was built more than 100 years ago to supply water to the sawmill and was later stocked with invasive species. Such existing conditions challenged the design team to make trade-offs between four occasionally competing priorities, according to architect Burt Gregory of Mithun. Those priorities were "education, experience, economics, and environment." The design team decided to keep the pond and the wetland habitat that goes with it.

Low environmental impact was such a high design priority, it would be safe to say the loggers who previously occupied the land had a substantial role in the plan of the site. All of the campus buildings were positioned on level areas that had been previously cleared. Because of the desire to limit construction impacts and vehicular access, clusters of buildings were placed at or near property perimeters. Once the general outlines of the logged areas were established, an exhaustive inventory of trees was conducted, and the dimensions and orientations of the buildings were adjusted. After the site was cleared of invasives and underbrush, the buildings were staked. In general, structures were placed on a north—south axis at the northern edge of "solar meadows" in order to maximize passive solar gain.

One of the most dramatic natural features of the site is a steep ravine. It would have been tempting to lead kids down the slope so they could experience the changes in microclimate and the closeness of a fast creek, but the design team agreed that this would be coo great a threat to the health of the scream. Instead, they lobbied for a long suspension bridge over the ravine, one where kids could cake in a whole section of the landscape. The graceful metal structure is now one of the most popular places on site.

New trails, boardwalks, and bridges are threaded through the site to avoid sensitive habitat and natural systems. Primary pedestrian circulation follows a historic logging road, and trails are constructed using native soils. 14 important to make the transition from a standard country road to one that has been located so that you really do feel you are in a sanctuary," says Berger.

Bringing utilities into the site was a special challenge, since trenching and pipes can result in tree die-off due to dewatering. The problem was resolved by running utilities directly under the main paths through the site. Walking surfaces were raised off the forest floor so that lines could be buried with little disturbance to the existing root systems. The resulting paths, with gentle embankments, are at once connected and lifted from the forest floor. Construction access was strictly con-fined to circulation mutes, and crews literally swept them off as they withdrew from the site.

Students, visitors, and guests see recycled materials in new applications that enhance the beauty, usefulness, safety, and accessibility of the site and its buildings. Crushed recycled concrete is used for parking and walking surfaces to minimize runoff from pavement, and trail paving is made of a crushed recycled concrete aggregate base.

Bike racks were constructed on site using site-salvaged cedar logs. A walk-way connecting the main lodge and dining hall is built with plastic lumber, a natural-looking recycled material. A site-salvaged rock "rumble strip" at the dining hall warns sight-impaired visitors using canes that windows swing out from the side of the building. Patio pavers at the guest cottage are made of crushed re-cycled glass. At the parking lot, impact curb wheel stops are composed of mixed post-consumer and postindustrial plastics and auto-shredder residue.

As man-made landscapes like the organic garden mature within the larger natural setting, the impacts and responsibilities of humans can be better understood, according to artist Lorna Jordan, whose ideas served as a catalyst for the design concept in the beginning stages. "People who under-stand their own habitats are more likely to become stewards for those of other species," she says. - LA

As man-made landscapes like the organic garden mature, the impacts and responsibilities can be better understood.... "People who understand their own habitats are more likely to become stewards for those of other species"